Editor’s note: Paige Ouimet is Director of Research, Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise & Professor of Finance, UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School.

UNC-Chapel Hill’s Kenan Institute will offer analysis of the latest data this Friday. “After blockbuster job gains in January, more moderate numbers are predicted for February. Will the new employment report Friday deliver another surprise, and how will it affect expectations of a possible recession or even a ‘no landing’ scenario.

This story is TechWire’s weekly Deep Dive.

+++

CHAPEL HILL – The labor market is historically tight at the outset of 2023. There are two job openings for every unemployed person, the highest such ratio that has been recorded in Bureau of Labor Statistics data.1 And the trend appears to be deepening: The number of job openings increased in December for the third consecutive month.2

There is significant debate as to what is driving this imbalance. One line of thought points to more transient factors, such as COVID-19 health concerns and household wealth accumulated during the pandemic. However, longer-term trends – such as an aging population, years of reduced immigration, a long-term decline in labor force participation among men and a surge in early retirements – are also likely culprits behind this constriction of the labor supply.

Given the role of these longer-term trends, it seems unlikely that this tight labor market will loosen quickly. Firms need workers now. Moreover, we have seen a dramatic transformation in what workers expect from their jobs – and when these needs are not met, workers are quitting in droves.

Below, we survey several of the factors that are essential to understanding the dynamics now at play in regards to the supply of workers; previously, we published a Kenan Insight providing similar analysis to the demand side of the labor market. As the Kenan Institute moves into its 2023 grand challenge, these are some of the trends we’ll unpack and monitor over the course of the year, as we seek to understand how employees and employers alike are navigating these conditions.

Good news, job seekers: Triangle openings on the rise after February dip

Demographics

The changing demographics of the United States are having a profound effect on the labor supply in the nation. The population is aging, with baby boomers reaching retirement age and those ages 65 and over expected to outnumber those ages 18 and under by 2034.3 This shift in the age distribution of the population is expected to continue to have a significant impact on the U.S. labor supply. As the proportion of older individuals increases, the fraction of people who are willing or able to work is likely to decrease. And while it is possible to increase the participation rate of older workers – it declined during COVID and has not recovered – it is unlikely to increase enough to fully counter the aging of the population. This demographic pattern is unlikely to be reversed in the near term. On average, there are 1.7 births per woman in the U.S., a rate that will lead to a shrinking population without a sharp rise in immigration levels.4

Health Factors

Another set of factors affecting the supply of workers involves trends that have taken away or limited the ability of some individuals to work. Long COVID refers to long-standing effects from COVID-19 that may include fatigue and brain fog; roughly 30% of those with the condition experience symptoms that impact their ability to work. As a result, long COVID may reduce the U.S. labor force by as much as a full percentage point.

Additionally, drug addiction, particularly opioid addiction, has reached crisis level in the U.S. over the last two decades, which has substantially affected labor force participation. Much of the growth in opioid addiction has been linked to doctor-prescribed opioids during a period when the medical establishment was underestimating the addictive nature of these prescriptions. Estimates indicate that individuals who received an opioid prescription were 3.7% less likely to be employed five years later, as compared with a similar individual being treated for the same diagnosis but who did not receive an opioid prescription.5

Immigration

Because of the COVID pandemic, as well as policies implemented by the Trump administration, the U.S. has witnessed a dramatic decline in international immigration. In 2021, about 245,000 people from outside of the country migrated to the U.S. – nearly a 50% decline from the previous year, and less than a quarter of the 1 million international migrants we had in 2016.6 Immigration to the United States does appear to be on the rebound, as the U.S. returned to those 2016 levels (and received just over a million immigrants) between July 2021 and July 2022.7 However, even with this uptick, we remain below the level of immigrants needed to sustain the dismal population forecasts from the census.8

The economic literature has generally found that immigrants help contribute to innovation.9 Studies have found that immigrants are more likely to start new businesses and to file patents, both of which can lead to greater economic growth. Additionally, immigrants tend to have diverse skills and backgrounds, which can bring new ideas and perspectives to the workforce. Research from UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School Professor Abhinav Gupta demonstrates that greater barriers to immigrant labor mobility – or the ability of workers to switch between firms – also results in a decrease in entrepreneurship and new firm formation.

An influx of immigrants is especially important given the aging U.S. population described above. 2021 marked the first year since the Great Recession that the U.S. birth rate has increased; even so, the total fertility rate remains well below replacement, or the number needed for population numbers to offset death rates.10 Immigration thus remains an essential economic tool for the U.S. to maintain a sufficiently large workforce.

Childcare

An increase in the number of women entering the labor force was a major factor in the changing demographics of the U.S. labor supply from the 1970s to 2000. Women are now more likely to pursue higher education and pursue a career, and account for more than half (50.7%) of the college-educated labor force.11 This has created new opportunities for women in traditionally male-dominated occupations – and also stimulated the U.S. economy. A 2017 report from S&P Global estimated that continued reductions in gender inequality (and subsequent increases in women’s labor force participation rate) could lead to as much as a 5%-10% increase in nominal U.S. GDP, as well as help offset the effects of an aging workforce.12

However, as the chart below illustrates, the prime age (25- to 54-year-old) female participation rate has stagnated over the last 20 years. A lack of access to childcare is likely to be one of the drivers of these trends and could even potentially reverse gains made by women in recent decades.13 One paper from UNC Kenan-Flagler Professor Elena Simintzi demonstrates that earlier access to childcare significantly increases employment and income growth among new mothers; a separate piece of research shows that industries with greater access to childcare have a smaller gender pay gap.14 Separate research from the Pew Research Center found that childcare was a factor for roughly half of those who quit their jobs in 202115, while a team based at Northeastern University documented significant issues in childcare access, especially for women of color and women in low-income households.16

Flexibility and Preferences

Lockdowns provided a multitude of workers with time off from work, which many used to reevaluate what they want from their jobs. At the same time, there is also a culture shift occurring as younger generations enter the workforce. Taken together, there has been a significant change in what employees want from their jobs. Employees want to be their authentic selves at work, and to feel that their work does not conflict with their personal lives. As the “great resignation” began in 2021, 57% of employees who quit that year reported feeling disrespected at work as a major reason behind their decision to leave.17 Employees are also increasingly demanding that their employers have a sense of purpose beyond just profit maximation.

With the rise of the gig economy, another major trend in worker preferences has been an increased demand for flexibility. Contract work and gig employees are increasing, challenging the one-size-fits-all standard in 9-to-5 work. A 2020 study by the ADP Research Institute conducted shortly before the pandemic found that the number of gig workers had increased 15% since 2010.18 The work-from-home revolution necessitated by the pandemic also showed employees that much of their work could be done away from a physical office or even asynchronously. Subsequently, more workers desire an option to work from home, work more flexible hours or set their own schedule.

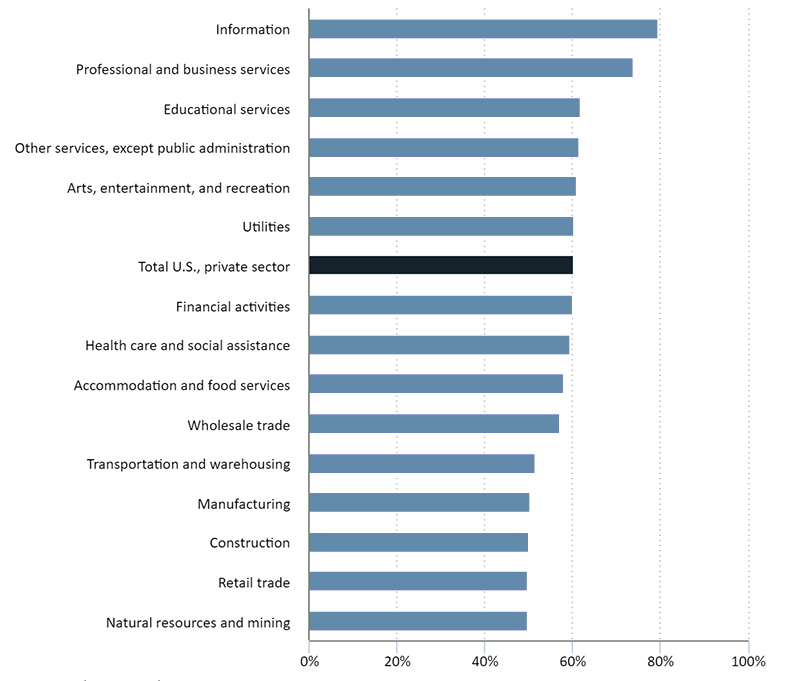

Percent of private sector establishments with increased telework that expected the increase to continue after the COVID-19 pandemic ends, 2021

This has created issues for employers, who face difficulties sustaining workplace culture and monitoring their work-from-home employees. As a result, employers are increasingly resisting the work-from-home demands of their workers and require at least some degree of in-office presence. The question remains, however, if the tightness of the labor market will undercut employers’ ability to bring their workers back to the office.

For employees or those seeking employment, a greater menu of options is now on the table. The gig economy allows for highly flexible work – albeit work that often lacks the benefits that traditionally accompany employment, such as health insurance. The rise in working from home means that far more workers no longer need to live in the same city, state or even country as their employers. The overall distribution of workers’ preferences is thus shifting to accommodate these new possible forms of employment.

Conclusion

This grand challenge marks the Kenan Institute’s primary research initiative in 2023. To address it in a holistic and comprehensive manner, we’ll draw upon a variety of approaches over the course of the next year, including Kenan Insights and commentaries, video content, webinars and in-depth conversations with our experts and 2023 Distinguished Fellows. Our turn to the subject of labor markets reflects the topic’s near-universal importance – as well as the severity of the tumult that faces employees and employers alike – and we look forward to seeing where our exploration leads.

To learn more, visit https://kenaninstitute.unc.edu/tag/workforce-disrupted.

(C) Kenan Institute

1 As of January 2023. History of job openings goes back to 2000.

2 Ciment, S. (2023, February 1). Labor Market Stays Hot as Job Openings Grow to 11 Million in December. Yahoo! https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/labor-market-stays-hot-job-160223973.html

3 America Counts Staff. (2019, 10 December). 2020 Census Will Help Policymakers Prepare for the Incoming Wave of Aging Boomers. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/12/by-2030-all-baby-boomers-will-be-age-65-or-older.html

4 Paulson, M. (2022, July 8). Measuring Fertility in the United States. Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2022/7/8/measuring-fertility-in-the-united-states

5 Ouimet, P., Simintzi, E., & Ye, K. (2020, August 14). The Impact of the Opioid Crisis on Firm Value and Investment Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3338083 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3338083

6 Rezal, A. (2022, February 22). International Migration to the U.S. Plummeted Last Year, Census Finds. US News. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/2022-02-07/census-international-migration-to-the-u-s-plummeted-in-2021

7 Knapp, A., & Lu, T. (2022, December 27). Net Migration Between the United States and Abroad in 2022 Reaches Highest Level Since 2017. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/12/net-international-migration-returns-to-pre-pandemic-levels.html

8 Frey, W.H. (2023, January 4). New census estimates show a tepid rise in U.S. population growth, buoyed by immigration. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/new-census-estimates-show-a-tepid-rise-in-u-s-population-growth-buoyed-by-immigration/

9 Bernstein, S., Brown, A., & Brown, G. (2019). Immigrant Entrepreneurship: An American Success Story. Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise. https://www.kenaninstitute.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ImmigrantEntrepreneurship_05312019.pdf

10 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, May 24). Births Rose for the First Time in Seven Years in 2021 [Press Release]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/20220524.htm

11 Fry, R. (2022, Sept. 26). Women now outnumber men in the U.S. college-educated labor force. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/26/women-now-outnumber-men-in-the-u-s-college-educated-labor-force/

12 Bovino, B.A., & Gold, J. (2017). The Key to Unlocking U.S. GDP Growth? Women. S&P Global. https://www.spglobal.com/_Media/Documents/03651.00_Women_at_Work_Doc.8.5×11-R4.pdf

13 McKinsey & Company. (2021). Women in the Workplace. https://leanin.org/women-in-the-workplace#key-findings-2021

14 Simintzi, E., Xu, S., & Xu, T. (2022). The Effect of Childcare Access on Women’s Careers and Firm Performance (Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise Research Paper No. 4162092). SSRN.

15 Parker, K., & Horowitz, J.M. (2022, March 9). Majority of workers who quit a job in 2021 cite low pay, no opportunities for advancement, feeling disrespected. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/03/09/majority-of-workers-who-quit-a-job-in-2021-cite-low-pay-no-opportunities-for-advancement-feeling-disrespected/

16 Modestino, A.S., Ladge, J.J., Swartz, A., & Lincoln, A. (2021, April 29). Childcare Is a Business Issue. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/04/childcare-is-a-business-issue

17 Parker, K., & Horowitz, J.M. (2022, March 9). Majority of workers who quit a job in 2021 cite low pay, no opportunities for advancement, feeling disrespected. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/03/09/majority-of-workers-who-quit-a-job-in-2021-cite-low-pay-no-opportunities-for-advancement-feeling-disrespected/

18 Iacurci, G. (2020, February 4). Gig economy grows 15% over past decade: ADP report. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/04/gig-economy-grows-15percent-over-past-decade-adp-report.html