Editor’s note: Gerald Cohen is Chief Economist, Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise.

+++

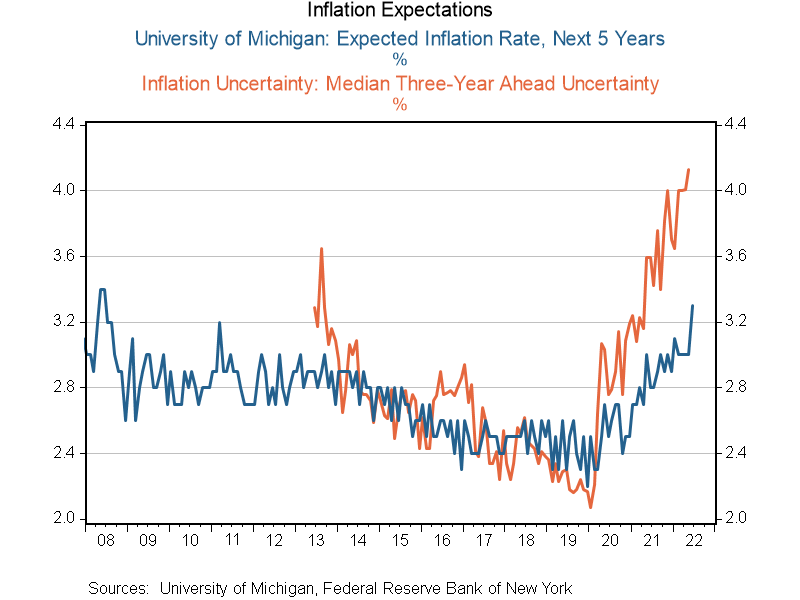

- The Fed got spooked by a 40-year-high inflation print and some uncomfortable readings on inflation expectations — which in my opinion are more important.

- As a result, it raised rates by 0.75 percentage point and forecast an increase to 3.375% by year end.

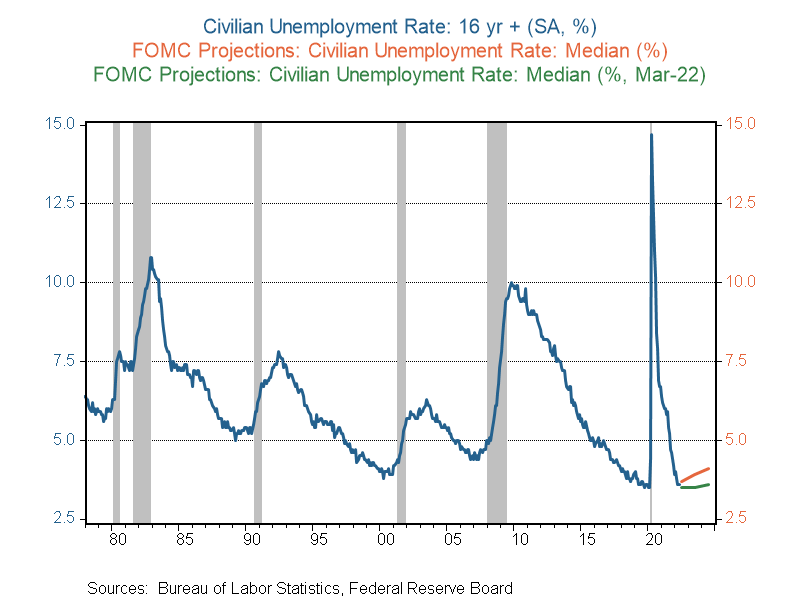

- While Chair Jerome Powell stressed that the Fed is not aiming to induce a recession, it penciled in an unrealistic quasi-recessionary unemployment forecast.

- Can the Fed convince consumers and businesses that it is going to keep inflation in check without causing a recession?

The Fed tried to show its inflation-fighting mettle by raising the federal funds rate, the short-term interest rate it directly controls, by 0.75 of a percentage point. This is the largest increase since 1994, though the funds rate remains at a quite low 1.625%, especially relative to the 8.6% inflation reading last week. The Fed seemed to be spooked by the inflation print — which, rather than declining as many forecasters (including myself) expected, rose to its highest level since 1981. More important, in my opinion, longer-term measures of consumer inflation expectations and uncertainty increased.

If households and businesses start acting as if inflation is permanently on a higher path, those expectations will become self-fulfilling. For example, workers will ask for fatter pay increases to keep up with inflation. These are likely to be passed on by businesses back to the consumers, which creates a vicious upward inflation cycle. Based on the experience of the 1970s and early 1980s, the Fed wants to avoid this at all costs — even if that means pushing the economy into recession, which despite Powell’s comments, is what its economic forecast now seems to be implying.

Along with the rate hike announcement, the Federal Open Market Committee published its Summary of Economic Projections, which took a knife to economic growth (cutting GDP growth by 1.1 percentage points in 2002 and by 0.5 point in 2023). Of particular note, it raised the unemployment rate forecast from essentially flat (green line in the chart below) to an increase from the current 3.5% (blue line) to 4.1% by the end of 2024 (orange line). The graph illustrates that unemployment rates never have a slow, steady increase — once they start to rise meaningfully, they shoot higher! Research has shown that when the unemployment rate increases 0.5 percentage point relative to its low over the previous 12 months, the U.S. economy is in the midst of a recession.1 So while the timing of the Fed’s forecast doesn’t meet that recession criteria, the magnitude does.

It is not clear if this quasi-recession forecast is the result of the current and expected rate hikes, the consequences of $5-plus per gallon of gas, falling stock and bond prices, or shifts in consumer and business sentiment. While these record gasoline prices are painful for many — in particular, lower-income households — the $250 billion-plus cost to American consumers is not enough to cause a recession in a $24 trillion-plus economy. Similarly, I estimate the impact of falling stock and bond prices will lower consumer spending by $325 billion, which even in conjunction with gasoline prices will slow growth but is not enough to create a recession.2

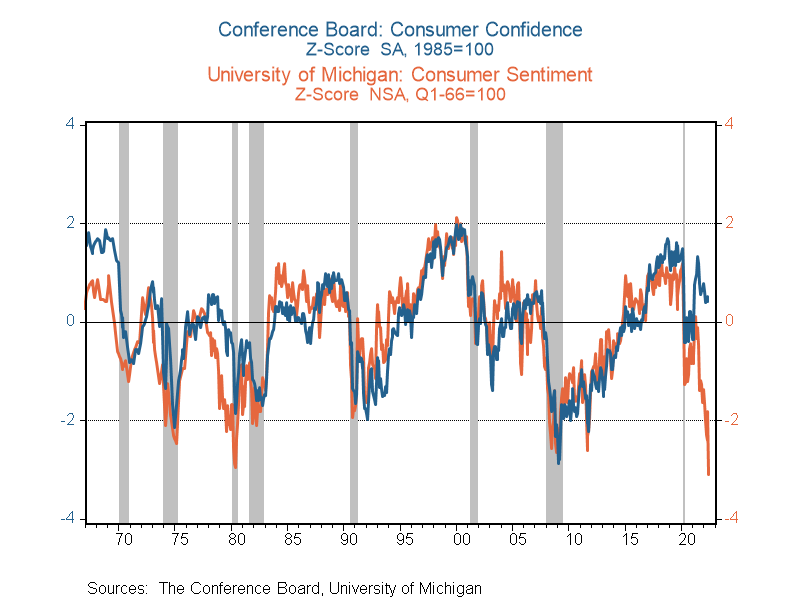

This leaves shifts in the psychology of consumers and businesses and/or Fed actions. Changes in consumer and business attitudes about spending or capital investment can be as self-fulfilling as the inflation expectations described above. If households get nervous, they stop spending at stores or restaurants. Those establishments then cut employment, which leads to lower spending and a vicious downward spending cycle. Unfortunately, we don’t have a great read on consumer and business psychology, and the indicators that we have are showing very mixed readings. One sentiment measure from the Conference Board (blue line) suggests a healthy reading at least through May, while the University of Michigan (orange line) was already at recessionary levels in May and hit a record low in early June. Even harder to understand are the drivers of shifts in psychology — which can come from higher prices or interest rates, market moves or Jamie Dimon’s talk of an economic hurricane.3

Where does this leave the Fed? Despite the drag from gasoline prices and market declines as well as some recessionary sentiment, the Fed has penciled in an additional 1.75 percentage points of rate hikes over the next six months. Some of this is being done to reinforce market expectations and sentiment. Still, many believe the Fed is way behind the curve. Raising rates, however, doesn’t solve supply chain constraints or increase oil production and refining capacity. In fact, increasing borrowing costs may actually hamper investment and cause business closures, worsening some supply constraints. Showing resolve against inflation by slowing demand enough without hampering supply and causing a recession is a challenging ask, especially in the current environment of extreme economic uncertainty.

2 https://www.nber.org/papers/w25959

(C) UNC-CH Kenan Institute