Edit’s note: This is part two of a debate about the economy from Kenan Institute experts. Access the first installment of this two-part debate here.

Given your earlier disagreement about the degree to which the U.S. economy is overheating, what role would each of you say the monetary policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic has played thus far – and how do you believe that response will evolve in the next year or two?

Greg: The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy response to the pandemic has been widely discussed, and its most recent statements suggestsome appreciation of the need for less accommodative monetary policy.1 However, a few interest rate increases in 2022 and a more rapid tapering of bond purchases will still leave monetary policy at extremely loose levels. To see this, consider the fact that economists believe it is real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) interest rates that most influence economic activity. And the recent level of the real fed funds rate is negative 4.60% – the lowest level on record!

Is US economy really overheated? UNC economist says ‘It’s boiling over!’

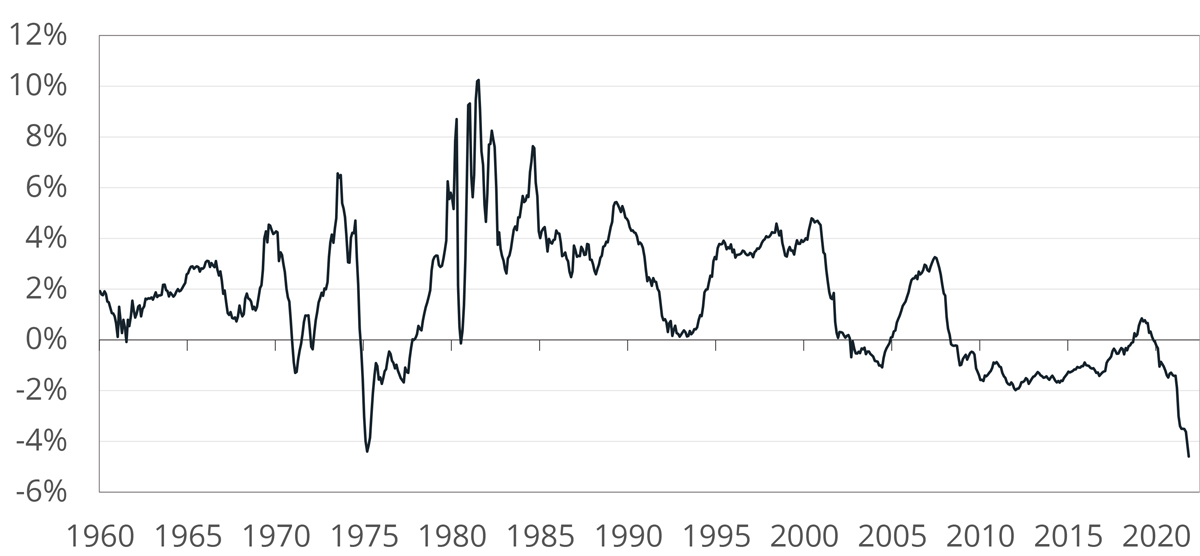

Gerald: This is a very challenging time for policymakers. The Fed needs to show its resolve to fight inflation so that expectations don’t shift, but if inflation is about to abate, then a significant tightening could throw the economy into a recession. Let’s say the Fed raises the federal funds rate to 4.75% so that the real funds rate is now slightly positive. What happens if inflation falls to 2%? Real interest rates become very restrictive, especially since the neutral funds rate may be closer to zero as illustrated by recent history (see Figure 1).2 A similar argument goes for the output gap, if you think the economic is way overheated – a positive output gap of 5.9% – then the Fed should tighten massively, but what if it’s +0.2% (or even negative)? Lifting your foot off the accelerator as the Fed is doing may be much more appropriate.

Fig. 1: Real Federal Funds Rate

Sources: U.S. Department of Commerce, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Inflation is calculated using the 12-month change in the core PCE deflator.

Sources: U.S. Department of Commerce, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Inflation is calculated using the 12-month change in the core PCE deflator.What about fiscal policy – the purview of the taxing and spending authority? It has provided strong support for the recovery to date, but is there a risk it was too much?

Greg: On top of the unprecedented monetary stimulus of the last two years, the U.S. has experienced a massive fiscal stimulus. This response was completely warranted in the early days of the pandemic and likely saved millions of jobs and personal bankruptcies. But the continued stimulus through late 2020 and especially 2021 were excessive (admittedly, with hindsight).

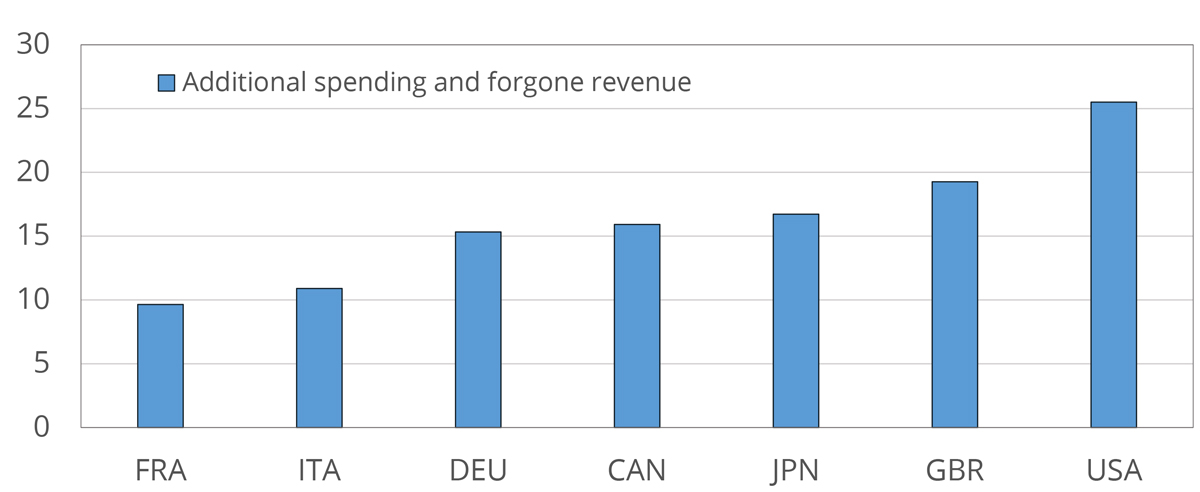

It is hard to measure the exact economic impact of fiscal stimulus, but it is certainly in the many trillions of dollars. An accounting by the IMF of fiscal stimulus around the world estimates that the U.S. provided support in excess of 25% of GDP through September 2021 (Figure 2). This enormous increase in household wealth, as much as the supply shortages of some goods, drove supply-demand imbalances in 2021. More important, the wealth effect will continue through 2022 – leading to continued risk of both a further overheating of the economy and further inflation.

Fig. 2: Discretionary Fiscal Response to the COVID-19 Crisis in G7

(Percent of 2020 GDP)

Source: IMF

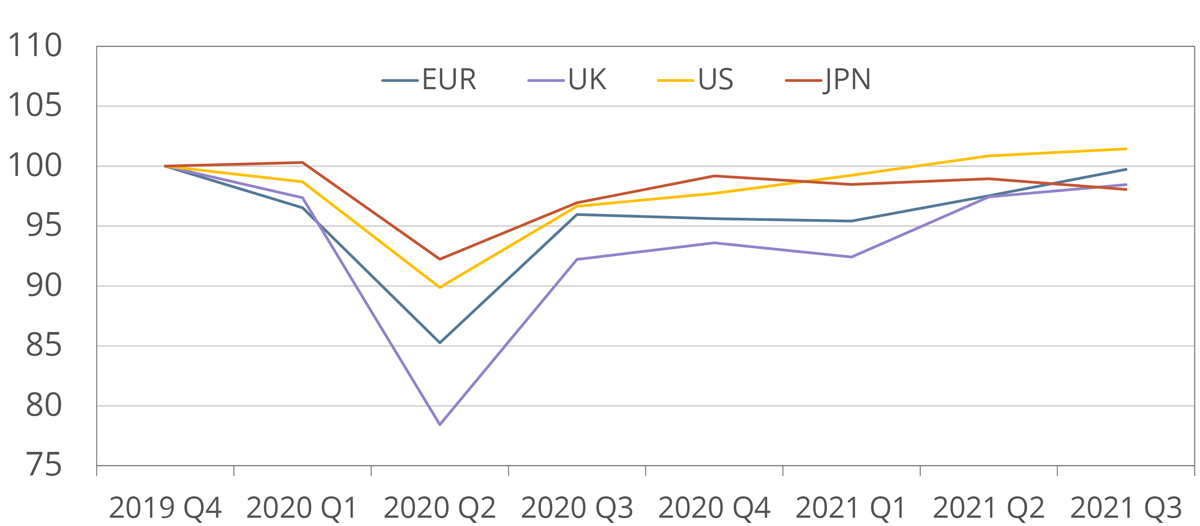

Source: IMFGerald: The U.S. fiscal response is one of the reasons why the U.S. had one of the shallowest recessions and strongest recoveries relative to advanced economy peers (Figure 3). I agree that the level of fiscal support should decline, but in contrast to the Fed, fiscal policy can use targeted policies to meet current challenges. For example, the expiration of the expanded child tax credit at the end of December can be seen as a needed tightening if the economy is overheated, or a painful loss of support for those workers who are having a hard time managing child care during COVID-19 because their jobs cannot be done remotely. Research indicates that underserved communities and those with lower educational outcomes are least likely to work remotely.3 Moreover, these same communities are least likely to have benefitted from stock market gains.

Fig. 3: Real GDP (2019 Q4 = 100)

Source: FRED

Source: FREDI think Greg and I both agree that we should have an expanded but means-tested child tax credit irrespective of the size of the output gap. However, our views on the output gap and inflation affect the need to find offsetting tax increases or spending cuts in order not to further stimulate the economy. And our challenging political environment raises the level of difficulty.

You mention the child tax credit, but what other recommendations do you have for policymakers to ease the current tensions in the economy without stifling growth?

Greg: I see two main priorities for fiscal policy. First is to implement policies that increase labor force participation. With a current and continued labor shortage, policymakers should adopt and expand programs (at least temporarily) that will pull potential workers into actual employment. These could include new childcare credits and other family-friendly policies, an expansion of the earned income tax credit, and mobility tax benefits for workers willing to relocate. In addition, a temporary increase in foreign worker visas could provide a nearly immediate positive shock to labor supply.

Second is to concentrate spending on increasing supply (i.e., productive capacity of the economy) and not on generating new demand. Overall, the message from this analysis is that decisions by policymakers (and businesses, for that matter) should be focused on how to increase supply, and less concerned about increasing demand. This suggests new programs of any sort should be deliberate in assessing both the type and timing of economic impacts.

Gerald: Policymakers should always be looking for ways to incentivize investment in productive capacity, but until COVID-19 is well behind us, there are households that have suffered disproportionally from the pandemic that will continue to need support. Without that support, the likelihood that they will permanently drop out of the labor force increases.

I agree with Greg on policies to increase labor force participation, but one other important opportunity we should be implementing is up-skilling. Regardless of whether we have a permanent decline in the supply of labor or a more temporary shift, making productivity-enhancing capital investments helps the economy in the long run. In order to take advantage of those investments, we need a more skilled workforce. Policies that increase skill levels can start as early as pre-K and run through community college and part-time credentialing programs as well as traditional higher-ed programs. These investments will raise educational levels across the entire population and thus increase potential output levels (i.e., productivity growth rates) for years to come. Some of these can have a positive effect in 2022, but effects are long lived for educational investments.

In this current climate, what steps should business executives take to mitigate the risks of a simmering economy?

Greg: Businesses should invest in productivity-enhancing capital now. If labor shortages continue, businesses will increasingly need to shift toward more capital-intensive production. Firms adopting technology in recessions or when faced by labor shortages is not new.4 One of the lessons from COVID-19 is that technology adoption can also reach the types of businesses and jobs that have not been impacted much by technology adoption before. Previously, labor markets that were specializing in manufacturing and routine tasks reallocated low-skill labor into service occupations which were not impacted by technology adoption. During the COVID-19 pandemic, labor shortages and perhaps a shift in customer demand (e.g., social distancing preferences) have caused many small businesses to adopt technology, which has now replaced many low-skill jobs in the services sector.5

Recession coming? Odds go up as Fed moves to raise interest rates

Businesses need to brace for the possibility of much higher interest rates. If, in fact, the economy is as overheated as my arguments suggest, there is asymmetric risk to the upside for both short-term and longer-term interest rates. Businesses should extend the maturity of fixed-rate debt either through new terms or synthetically (e.g. fixed-for-floating interest rate swaps).

Gerald: Businesses shouldn’t be afraid to raise wages. If you believe that quality workers are waiting on the sidelines, then incentivize them to return to work through higher wages. In most cases, technology is not a perfect substitute for labor but a complement to labor, especially in the service sector. If demand shifts back to services, businesses are going to need those workers.6

Businesses need to focus even more on recruiting, retention and training. Anecdotally, businesses are increasingly open to new hires that would not have been considered prior to COVID-19, such as part-time workers, high school students and less-qualified applicants. This flexibility will need to continue and likely expand further. Investing in training for both these new less-skilled workers as well as the existing workforce can reap productivity benefits and increase worker morale. Increasingly, businesses must also meet needs of existing workers including long-term remote work options, childcare assistance and flexible schedules, to name a few.

Thank you both. You have provided much for everyone to consider and I’m confident our audience has benefited from this thoughtful exchange.

While the roadmap ahead is challenging, it is critical that policymakers and business leaders keep a close eye on the data and be poised to adjust. Flexibility – operational and intellectual – is most valuable when we are facing considerable uncertainty.

And be sure to stay up to date on the hottest topics related to business and the economy by subscribing for our weekly Kenan Insights – you can find the option to do so in the footer of this page.

(C) UNC-CH

1 See, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20211215a.htm

.2 Note how the real Federal funds rate peaked at less than 1%, which caused a meaningful slowdown in interest rate sectors such as housing and overall economic activity. For more details see https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2017/february/three-questions-on-r-star-natural-rate-of-interest/

4 See, for example, B. Hershbein and L.B. Kahn (2018), Do Recessions Accelerate Routine-Biased Technological Change? Evidence from Vacancy Postings, American Economic Review 108(7), 1737-72. Also, J. Bena, H. Ortiz-Molina, and E. Simintzi (2021), Shielding Firm Value: Employment Protection and Process Innovation, forthcoming Journal of Financial Economics.

5 I thank my colleague Prof. Elena Simintzi for insights on this topic.

6 Acemoglu, D., and D. Autor, 2010, Skills, Tasks, and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings, NBER working paper 16082.